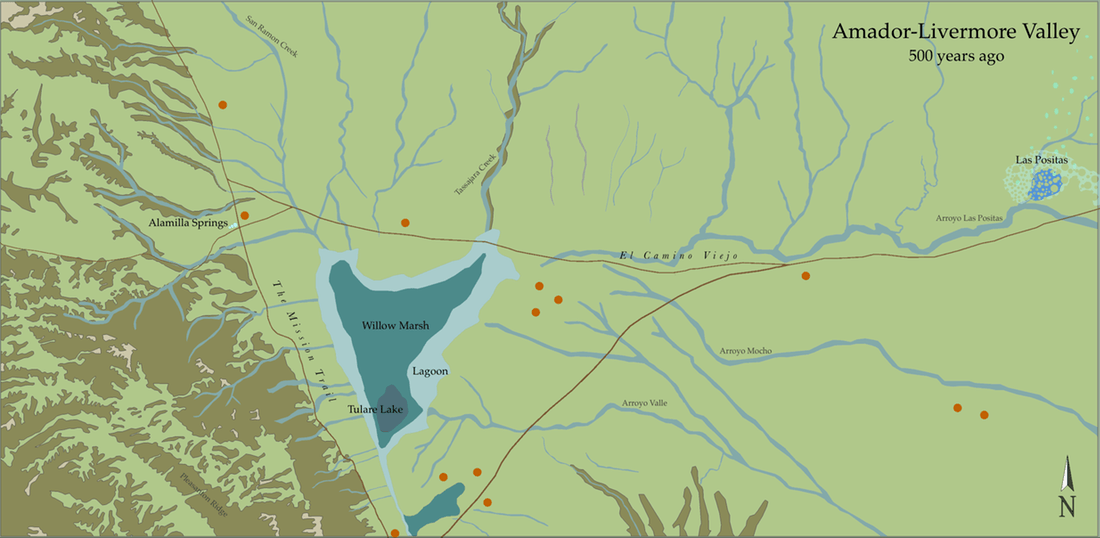

All of our information for this time period comes from archaeological digs, soil samples, and the diaries of the earliest explorers. The first Europeans to set foot in California arrived to what they assumed was an untamed wilderness. However, the natives were very skilled at managing their environment. They harvested seasonal fruits and vegetables, fished, organized hunts, established trade networks, and implemented prescribed burns on the land to increase vegetation output and encourage variety.

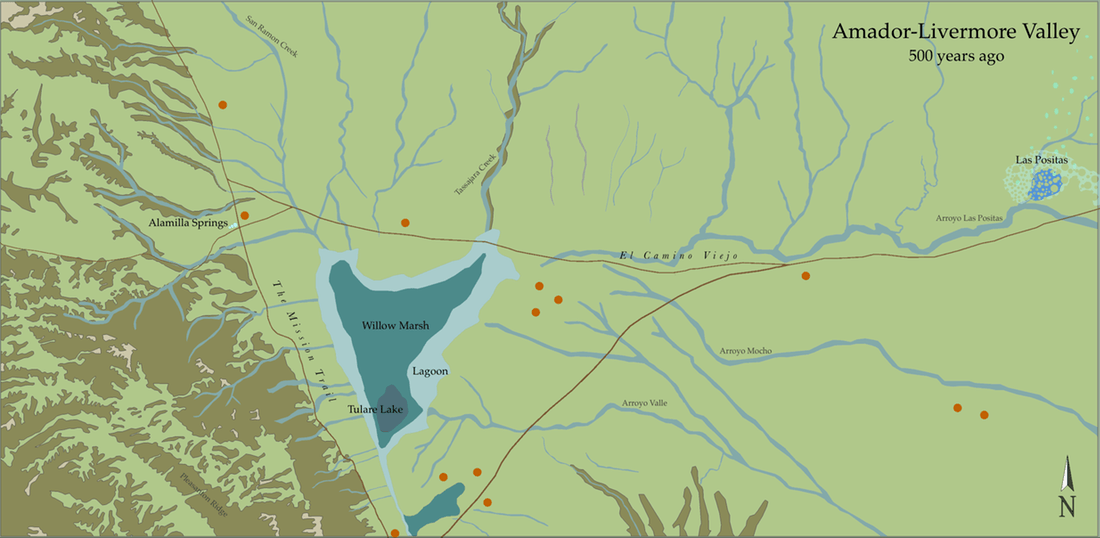

Wetlands dominated the landscape. In a very rainy season, they stretched all the way north toward San Ramon, and east toward Livermore. Seasonal rains fed vernal and perennial creeks, which emptied onto the valley floor. Depressions in the ground created a large, permanent lake at the heart of the valley, as well as smaller pools of water, such as those found at Las Positas. These lakes spilled onto the flatlands around them, creating vast marsh complexes, complete with thick beds of vegetation and wet meadow. The additional water also pushed up the water table in the enormous aquifer under the valley, forcing vernal and perennial springs to sprout throughout the area.

The freshwater marsh complex, which included thousands of acres of seasonal wetland, was once one of the largest in the bay area. Las Positas was a smaller, alkaline (saltier, acidic) wetland complex, a small part of which still exists today. Together these marshes hosted hundreds of species of birds and aquatic life, in addition to feeding the animals and human populations around them.

Trails criss-crossed the valley in every direction, connecting trade networks, hunting grounds and migration routes. The trails featured in the above map suggest only three of the major routes that connected Amador-Livermore Valley with the valleys around it. The trails going east to west, would one day become part of a trade route from Los Angeles called El Camino Viejo, or the Old Spanish Trail, while those going north to south became part of a north-south trail connecting the local missions to their farming lands.

On this map Alamilla Springs is highlighted because it was here that Jose Maria Amador, the first European to settle in the valley, would eventually build his house. The springs were at the cross-section of two major routes through the valley, and the crystal clear, fresh waters provided refreshment for travelers and animals. Alamilla Springs is where Dublin would one day have its start.

Indigenous peoples inhabited this valley for thousands of years. The orange dots on the above map symbolize native settlements. Although it is impossible to know the exact locations of such villages, or how many there were, we know that valleys all over California housed sizable populations. We also know that settlement locations shifted according to available resources, natural disasters, diseases, and war.

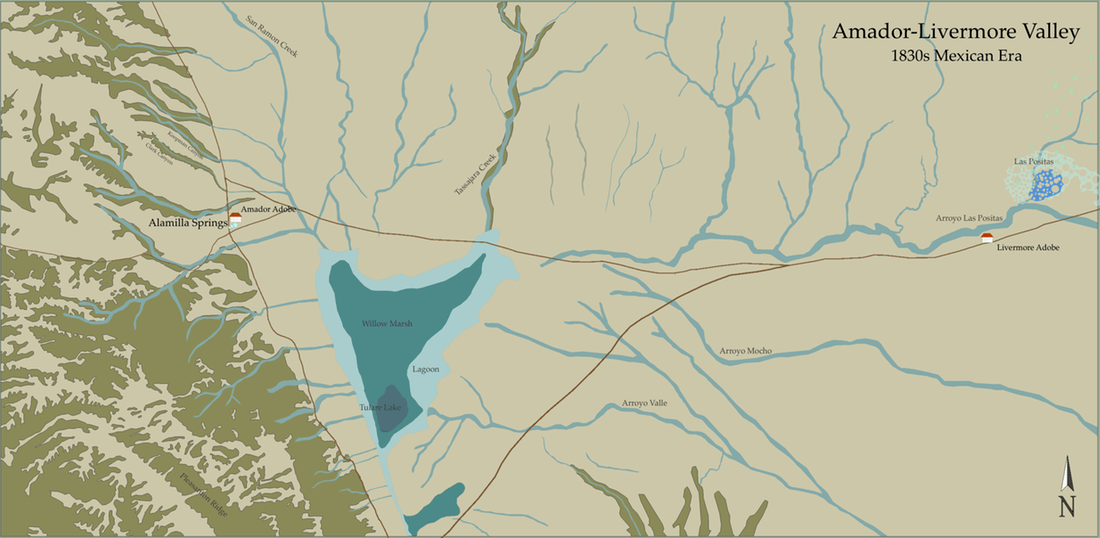

By 1821, when Mexico won independence from Spain, tremendous changes had taken place all over California, altering the landscape forever. Europeans that set foot on the coast brought everything from home: their personal belongings, plants, and animals. With them also arrived unseen microorganisms, such as bacteria and disease, that were completely foreign to California, its animals and native population, as well as its microclimates and endemic vegetation. Again using archaeological digs, soil samples, and the diaries of explorers, we know that within a short period of geological time, perhaps decades, all but the hardiest Californian plants, animals, and indigenous populations were taken over by their European counterparts.

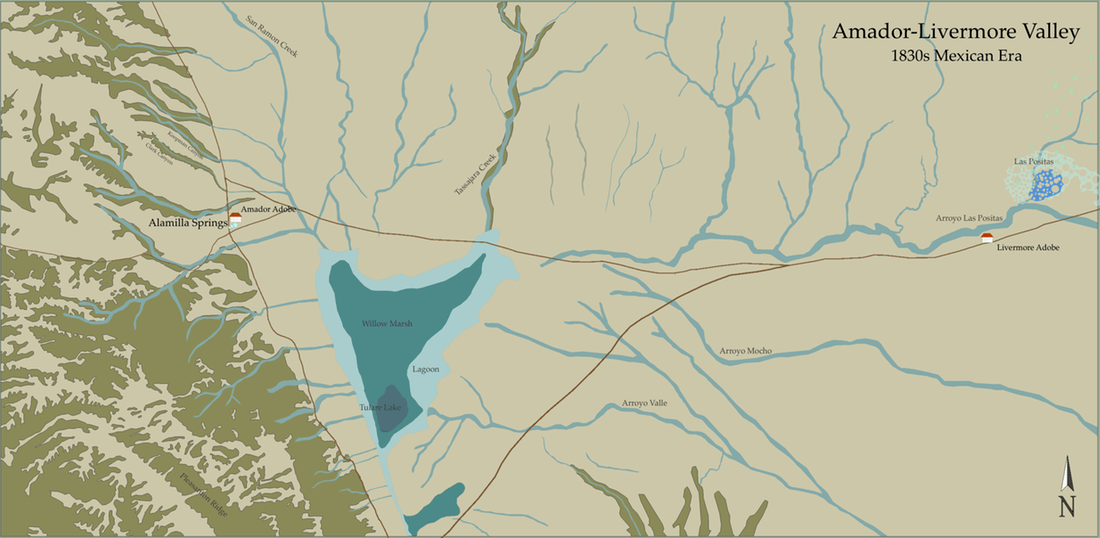

In the map above, all of the aboriginal settlements are gone, but skirmishes and competition for resources continued between natives and newcomers. Natives that did not want to live with and work for the missions, moved further inland, to the interior of California.

Foreign trees, bushes, fruits and vegetables thrived in California's climates. Also, native perennial grasses, which kept much of California's hills green year-round, died from the onslaught of Mediterranean annual grasses, which turn golden brown as they dry out in summer.

In the late 1820s, Jose Maria Amador built the first adobe in the valley, it was situated between Clark and Koopman Canyons, near the sulphur springs. But within a few years he built a new residence, near Alamilla Springs. Amador managed the pasturelands for Mission San Jose, a territory that included the entire Amador-Livermore Valley. He employed a number of natives to help him work the mission lands.

In 1834 secularization of the missions began. This involved selling to the public all of the lands that they owned. As a result, Amador-Livermore Valley was slowly divided into immense plots of land called ranchos. The boundary lines of ranchos were often demarcated by natural features in the environment, such as tree lines, hills, springs and creeks. Amador received his land in 1834. Robert E. Livermore was granted his land in 1839, building an adobe on the other side of the valley. For a short time the remaining ranchos were unoccupied (their owners lived elsewhere), and used mainly as pastureland.

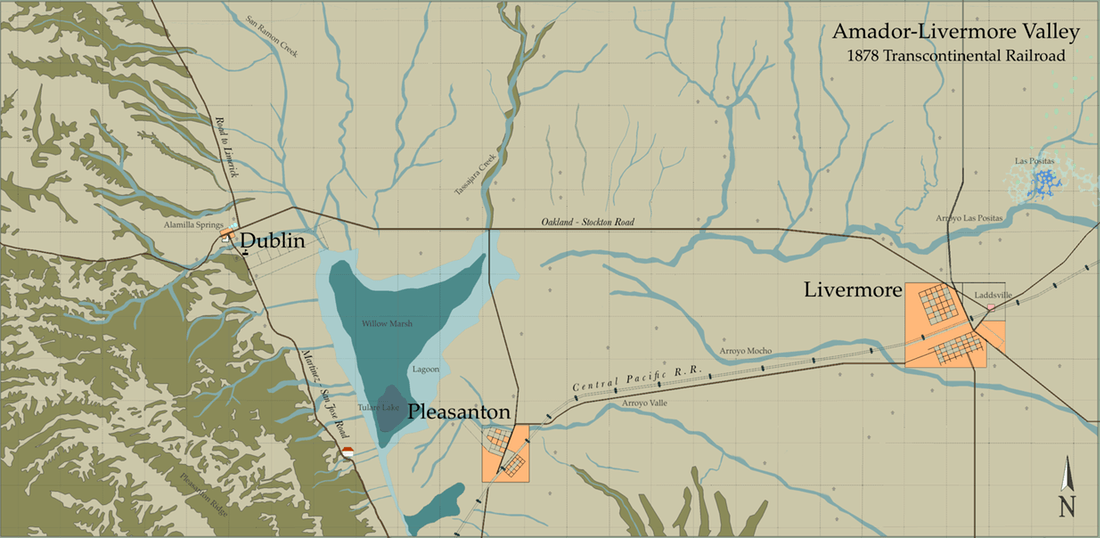

In 1849 California was under American military control, it was still a year away from statehood, and enormous ranchos marked the boundaries of land ownership on maps; but then the Gold Rush of 1849 brought newcomers to California at an unprecedented pace. They bought land when they could, or illegally settled on it when no owners were sight. Within a few years of the Gold Rush, houses dotted the landscape of our valley and towns began to form. On the map above we can see that the wet marshlands and some of the rancho boundaries shaped the patterns of settlement and determined the main routes through the valley.

A large portion of Amador's Rancho San Ramon, nearly everything visible on the map, was owned by the Dougherty family by 1853. Therefore, much of today's Dublin remained farmland, in the hands of one family, for several decades. The Dougherty family opened the first post office in our area in March, 1860.

The village of Dublin was first mentioned in San Francisco's Daily Alta in 1865. It was at the crossroads of two major stagecoach routes in and out of the valley, north to south and east to west. What started with Alamilla Springs and Jose Maria Amador's single adobe, became a small town with a church, school, general store, inn, and post office by 1865.

Alisal, to the south, also developed as a town along trade routes from the eastern edge of the valley down to San Jose. Named after a grove of trees, the Alisal covered a wide area. John W. Kottinger built a house here in 1851. By 1865 the town boasted a school, two stores, hotel, blacksmith and carpenter. Native Americans were also attracted to the area, previously the site of Coastanoan settlements. To various groups of Indians, the Alisal became a symbol of refuge and revitalization for their displaced communities. It is difficult to know the exact location of the pioneer and Native American settlements, but based on old maps and accounts we have an approximate idea.

Founded at the juncture of the roads going east from Dublin and Alisal, Laddsville was the endeavor of Alphonso Ladd. He wanted to build a community, so he started in 1864 with a large parcel of land. Within a couple of years there was a bustling town with hotels, several businesses, and a school.

Additional items to note:

Inspired by the Tompson & West Map of 1878, this map of the valley highlights the railroad, developing towns, contemporary survey lines, and many of the dirt thoroughfares that created the major routes we use today.

In the early 1860s a grand plan commenced to build a Transcontinental Railroad, connecting the east coast with the west coast of the United States. As it became evident that the tracks would route through Amador-Livermore Valley, the founders of Pleasanton and Livermore created town plans that incorporated the railroad. Pleasanton was established in 1867, and Livermore in 1869, the same year that the railroad laid the tracks. Thus, the towns of Pleasanton and Livermore became part of a national (transcontinental) network. These towns bustled with trade, and their populations grew steadily, luring new businesses, and attracting more citizens.

Dublin, on the other hand, was situated on the other side of the marsh, and in front of a steep grade that discouraged railroad developers. By 1878 Pleasanton flourished with a population of 550, and Livermore 950, but Dublin's was just over 100.

Also noticeable on the map are new survey lines that criss-crossed the ranchos, subdividing the land according to points on the compass, rather than following the natural features of the land. Whereas the ranchos were huge and land-ownership was in the hands of a few, this smaller, grid system was meant to facilitate land-distribution to many, and promote smaller, family-owned farms. At this point, nearly every square on this grid had a house on it or was claimed for farming, or land development or future investments.

What happened to Alisal, Laddsville, and Amador's adobe?

Alisal continued to exist, and was still attracting Native Americans; however the location of the settlement shifted further south (not on this map).

In September 1871 the business district of Laddsville was badly hit by fire. With the thriving new town of Livermore just down the street, the businesses moved and Laddsville never fully recovered. The land around it, and the town itself, was eventually incorporated into Livermore. Today's Ladd Avenue in Livermore is a reminder of where the town used to be.

Amador's adobe and a large portion of his nearby land was purchased by the Dougherty family. They resided in the adobe until 1861, when an earthquake struck, destroying parts of it, and the family decided to build a wood framed house.

The most noticeable aspect of this map is that the enormous fresh water marsh is gone. Marsh drainage began after 1880, and it took a few decades for the perennial lake to finally disappear. The need to drain wetlands was part of a national and global mindset that went back centuries. Swamps and marshes were stigmatized as useless, gloomy, wastelands that harbored illnesses and evil. Therefore, at that time it was considered a step in the right direction for a community to transform worthless wetlands into productive farmland.

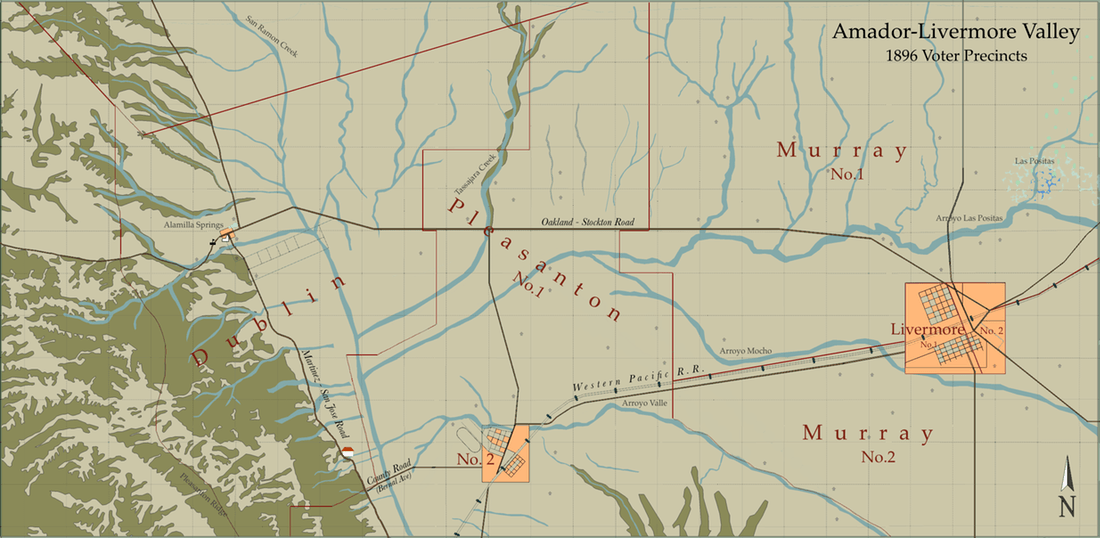

Voter precincts on this map reflect community ties that developed very closely with the land. The marsh had been a natural boundary that determined the directions of the roads, and, for several decades of settlement, there were no roads that crossed it. As a result, most of those who lived on the west side of it were connected with the village of Dublin. Pleasanton, with its large town and surrounding farmlands, had two voter districts, one for rural residents, and another for townsfolk. Livermore, on the other hand, had enough citizens to create two voting districts within the town's borders. All of the farmers to the east side of the valley were lumped into the general pools of Murray Township.

By this time the wealthy, philanthropic Hearst family purchased the land that is the site of today's Castlewood Country Club (not on this map), much further south of the County Road that would become Bernal Ave. Here Phoebe Hearst built her home, a grand estate called La Hacienda del Pozo de Verona. But more importantly she shared the land with the local Native American community, providing more time for the small settlement of Alisal to continue. The community was also often called the Verona Band, named after Verona Station, the train stop that was located by Hearst's estate.

In 1896 our valley roads were still made of dirt and automobiles were a new novelty, for those who could afford it. This meant that horses and bicycles (bicycle sales were booming in the 1890s) were the main mode of local transportation. This also meant that for anyone living on the outskirts of town, a trip to the local store or post office was a half day or all day event. A bicycle map, dated 1896, reveals the conditions of the major roads in the valley: the Dublin route to Livermore was in good condition and level, while the route between Pleasanton and Dublin was in fair condition, over rolling hills. Meanwhile, the routes out of the valley were in poor to fair condition, over steep hills. Imagine trying to ride a bicycle, without shocks, across dirt roads, just to send a message by mail.

Also noticeable on the map is that Dublin's Murray Schoolhouse was moved to higher ground, away from the flood plains.

In the 1930s the valley continued to experience growth, but not on the same massive scale as the towns and cities closer to the bay. Agriculture and ranching, which had been booming since the late 1800s, still provided big business because a majority of our area was prime farmland. Vineyards did well in the eastern and central parts of the valley. A cadastral map, dated 1910, shows water loving plants, such as sugar beets and hops were grown on the land formerly occupied by the marsh (our valley's hop yard was once one of the largest producer in the world). From the Pleasanton Hills to Patterson Pass, every bit of land was covered with orchards, vegetables, cattle, flower farms, or grain. With so many farmers and businesses drawing water from the same aquifer, water rights became a contentious issue, resulting in lengthy legal battles between land owners.

A map of Pleasanton, dated 1907, reveals a few road names, the newest train tracks, as well as plans for the canals. New roads were often labelled with a number on a map, but, locally, people named them after land owners, nearby destinations, or natural features. The additional train tracks through Pleasanton, and those east of Dublin, opened in 1908 and 1909. But the increasing popularity of the automobile, which did not rely on fixed routes, spelled doom for the railroads. As for all of the water that could no longer drain into a swamp, canals were needed for irrigation, and to channel the excess water during the rainy season.

By 1913 two manufacturers of automobiles in the United States were mass-producing cars; consequently, more of the general public was able to afford one. That same year the idea of a route that connected America's coasts came to fruition. It was called the Lincoln Highway. This transcontinental route was a huge milestone for America's highways because it raised awareness of road safety and increased funding for improvements. It was also a huge boon to Dublin because motorists would stop to fix their brakes just before or after making their way along the Dublin grade (click to see photo). A Lincoln Highway brochure from 1916 highlighted the requirements to make the journey from one coast to another ~ it took at least 20 to 30 days, going 18 miles an hour; at least $5 a day was recommended for gasoline and food; also, car owners were warned not to drive in the rain because much of the route was dirt.

In the mid 1920s the American Association of State Highway Officials began giving numbers to all of the major highways going through each state. The Lincoln Highway received two new names, locally it became State Highway 5, and nationally it became Route 50. In the 1930's today's Foothill Road was also given two names: State Highway 107 and US Highway 21.

This period was also when the Native American community of Alisal, or the Verona Band, experienced its demise. A fire broke out in the village in 1914, and it never fully recovered. Fortunately, a researcher named J.P. Harrington spent many years in the early 1900s speaking with locals and recording volumes about native customs and languages.

Much of the linguistic and cultural material he gathered, about local native populations, may be found at the John Peabody Harrington Collection

Our sleepy, picturesque valley got a wake-up call, after the United States entered World War II in 1941, when the Navy chose a site just east of the Dublin crossroads to build three large facilities. Camp Parks, then Camp Shoemaker, and finally Shoemaker Naval Hospital were built and occupied seemingly overnight, between 1942 and 1943. These bases, which included thousands of structures to house tens of thousands of men and women, collectively came to be known as "Fleet City." It was here that thousands of men every month were housed and trained before they were deployed. Camp Parks prepared Naval Construction Battalions (Seabees) to construct everything from hospitals to ports, while Camp Shoemaker readied sailors to fight and work on ships and bases throughout the Pacific. The Shoemaker Naval Hospital treated men and women for war wounds, illnesses as they went to, and returned from, combat and training. Fleet City grew to its largest capacity in 1945, accommodating over 70,000 people a month.

Komandorski Village was off base housing provided by the Navy for families, as well as staff who worked at Camp Parks, Camp Shoemaker and Shoemaker Naval Hospital. The Navy often had small housing complexes outside a base to allow civilians easy access to their temporary homes.

By 1946, with the war over, Camp Parks closed and Camp Shoemaker transformed itself into a Navy separation station. It was here that tens of thousands got their final discharge papers and started their journey home to civilian life. When that task was done, Camp Shoemaker and the hospital closed. Nearly all of the Camp Parks and Camp Shoemaker buildings were sold as scrap, and some of the material became houses, buildings, and churches throughout the Tri-Valley area.

Several airfields appear on topographic maps and aerial photos of the valley during the first half of the century. Some were mere landing strips, such as those north and west of Camp Parks, as well as one called Dow Airport, south of today's 580; they were very temporary, appearing on maps for just a year or more. However the largest airport, which changed shape and ownership several times, started off as a private air field at the northwest corner of Livermore. In 1942, as part of the war effort, this air field was Federally condemned and became the Naval Auxiliary Air Field. It was used as a refueling station, to transport the injured, and as a stop-over on long haul flights. Although not pictured on this map, a second Naval Air Field existed on the other side of Livermore too. This one was east of town, and the site later became the location of Livermore Labs.

What happened to the hop yard and the sugar company?

The ability to grow hops became more difficult as the water table, pressured from so much demand, lowered throughout the valley. Additionally, the market for hops dried up when Prohibition banned the production and sale of alcohol, from 1920 to 1933. The raising of sugar beets, however, continued in the valley well into the 1950s.

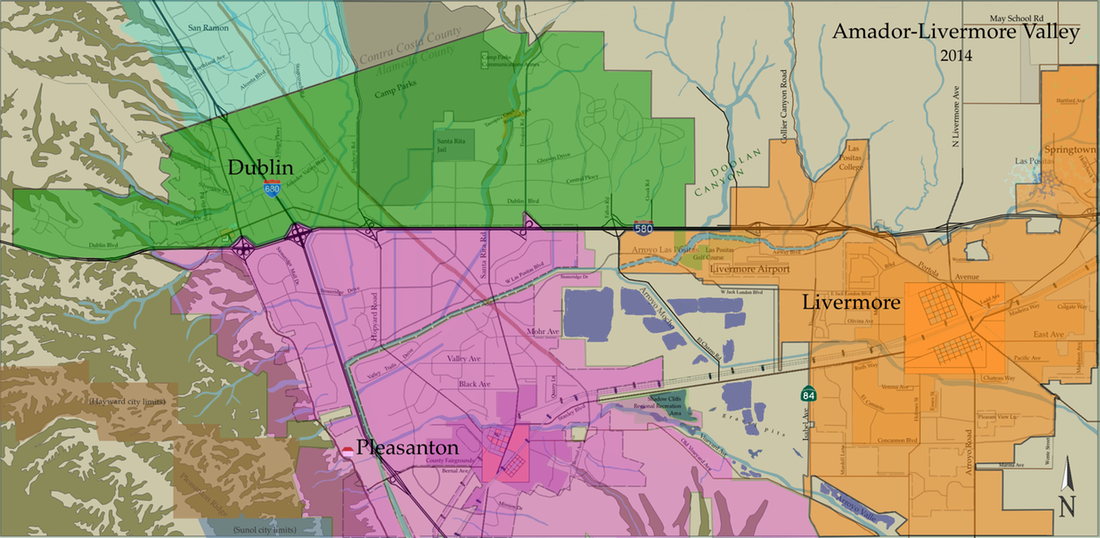

The onslaught of land-hungry pioneers in the 1850s was mild compared to that which entered the valley, and the rest of California, in the 1960s and 70s, when housing developments took root, transforming the hills and plains, farm by farm, into residential neighborhoods. Some farmers sold their land to developers willingly, while others gave up their farms begrudgingly, after having discovered they could no longer afford the taxes on their property. Farmers and ranchers were financially paralyzed by the skyrocketing taxes brought on by newly built, neighboring suburbs. It was not until the Williamson Land Conservation Act of 1965 that farmers in California were provided a financial safety net, a program created to provide relief to land owners at risk. But the act was passed too late for many, as the program was slow to grow and farms disappeared at an alarming rate.

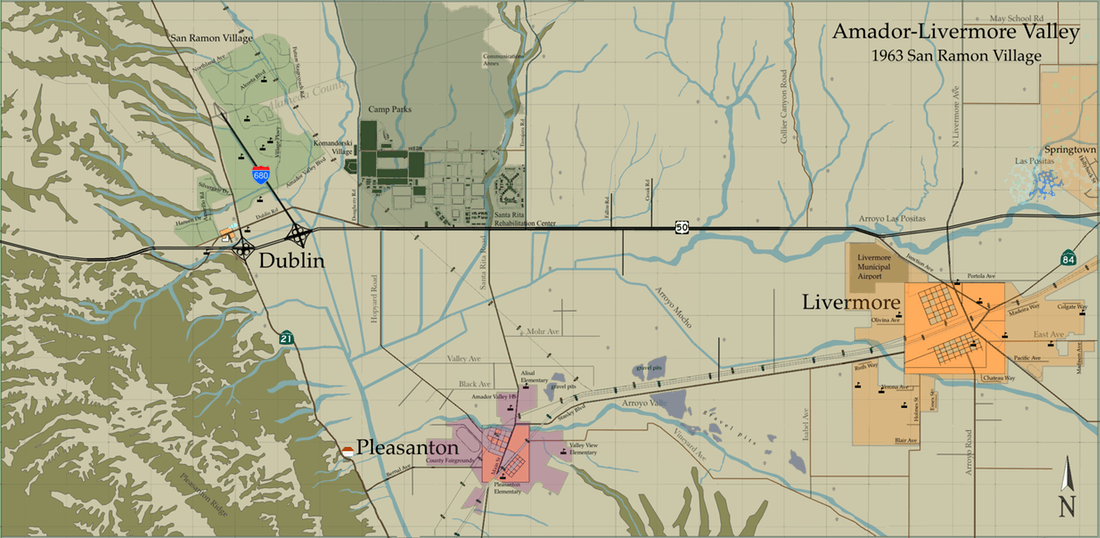

On the outskirts of Dublin housing developers built the large community of San Ramon Village in just a few short years. The sprawling clusters of neighborhoods straddled both sides of the county line. Builders advertised the serenity of the suburbs together with the close proximity of Bay Area cities. As one advertisement put it, San Ramon Village was "City-close" and "Country-quiet." The community was closest to Dublin, but the small town of Dublin was not yet incorporated (recognized as a governing entity) within the state. Therefore, San Ramon Village gained recognition, and was marketed and sold on its own merit, as a new place to live in Amador-Livermore Valley.

Meanwhile, the town of Pleasanton, incorporated in 1894, also lured community developers by the droves to its charming streets and fertile grounds. From 1960 to 1970 Pleasanton's population grew an astounding 336%, from 4,203 to 18,328, and it nearly doubled again in the next decade. The town's borders expanded tremendously, reaching east toward Livermore, annexing all of the land to the north, just below I580, and meeting Highway 21 to the west, sometimes to the chagrin of residents who considered themselves Dubliners.

During this time Livermore, incorporated in 1876, continued to be the largest town in the valley. The town had its growth spurt in the 1950s thanks in part to Livermore Labs (not pictured). From the 1960s to the 70s it doubled its population to nearly 38,000. The town's borders spread north to Springtown, east toward the hills, west to Pleasanton, and in the south it approached the wine region.

By 1960 there were about 1.6 million cars in the bay area. To accommodate all those drivers, Interstate 680 was created, and soon to follow Route 50 was widened and renamed Interstate 580. In the 1963 map above, I680 was at the earliest stages of construction.

What happened to the land occupied by the Navy?

In 1951 the Parks Air Force Base opened at Camp Parks, serving as a training center during the Korean War. Then in 1959 the area was transferred to the United States Army and remained under their jurisdiction until 1973. It was also at this time that some of the land was leased to the county and the Job Corps Training Center opened up, providing vocational and academic training to underprivileged youth. The Brig, or Disciplinary Barracks that had previously served Fleet City during World War II, was also leased to the county and repurposed as the Santa Rita Rehabilitation Center.

Komandorski Village became low income housing. It went through several phases in which housing stock was used, demolished, rebuilt and demolished.

Also, after World War II the city of Livermore leased the airport from the Navy, renaming it the Livermore Sky Ranch. By 1953 the Sky Ranch was the property of the city.

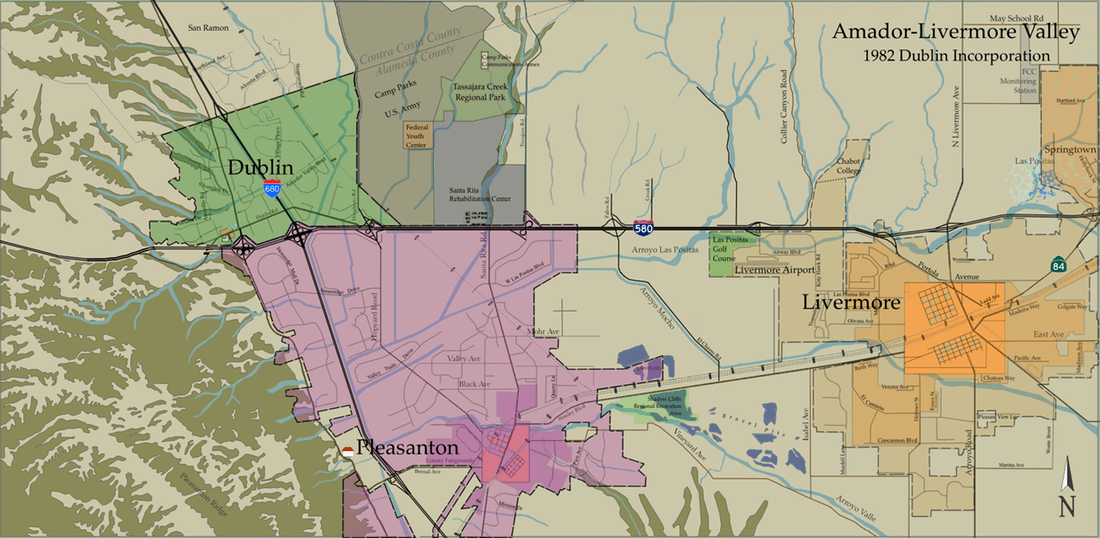

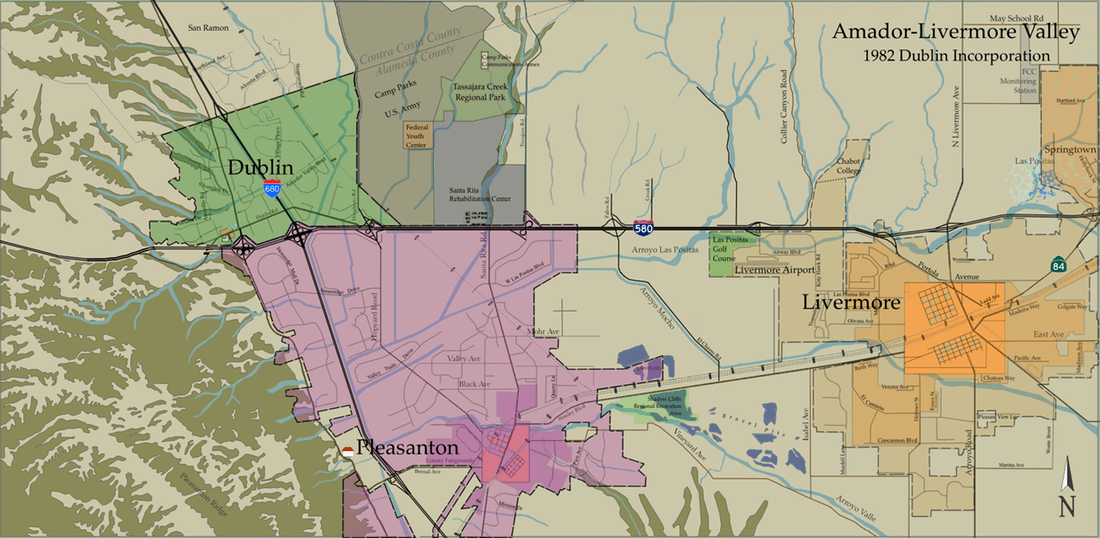

In 1981 Dublin and San Ramon Village residents voted for incorporation, and the area became the City of Dublin on February 1st, 1982. For many long-time residents who called themselves Dubliners, incorporation was an enormous triumph, after many decades of fearing annexation from neighboring towns and feeling like a small sideshow in a valley of flourishing communities. This map shows the boundaries of the new city in 1982 with a population that was over 13,000. At this time, the only undeveloped area within Dublin's borders lay between the railroad tracks and Camp Parks

Pleasanton continued to grow steadily, it's population over 35,000 in the 1980 census. Although the map above highlights only some of the major roadways, a quick look at maps from 1982 show many pockets within Pleasanton's borders without housing, but that rapidly changed in the coming years. As for Livermore, it remained the largest city valley, with a population nearing 50,000 at this time. The city's borders expanded, and the location of the airport moved west, in order to accommodate the growing neighborhoods.

Additional items on the map:

It's astounding to think how much has changed in the last 30 years. In 1982 we had to look at a physical map to figure out where we were and how to get somewhere. Today we have GPS and the internet to guide us. What else has changed?

Diversity - In 1980 the population of the Bay Area was just over 5 million, and residents of European descent made up a large percentage, 76%, of the population. Today the Bay Area has more than 7 million residents and is a much more diverse society; those of non-European descent, such as Asians and Hispanics, represent nearly half the population.

Sustainability - The Amador-Livermore Valley has experienced rapid growth along side the rest of the Bay Area, and in the last 30 years we have more than doubled our population. Today the combined population of Dublin, Pleasanton, and Livermore is just over 200,000. This population increase also represents greater competition for resources, such as land and water.

In the map above we see Doolan Canyon as one of the last swaths of open land between Dublin and Livermore. In the Spring of 2014 an urban limit line was drawn on the east side of Dublin, similar to the one that exists in the west hills of Dublin, preserving Doolan Canyon as a critical wildlife habitat. The initiative to continue to preserve Doolan Canyon as open space will go to the ballot boxes during the next election. Some residents view Doolan Canyon as a victory for the future of our open spaces, and others see it as a land bank for future home owners.

Water sits in most of the open gravel pits situated between Pleasanton and Livermore. The Zone 7 Water Agency, which supplies much of the water to Amador-Livermore Valley, has contracted to use this 'chain of lakes' for the storage and management of this precious resource.

Bicycle lanes and mass transit - Bike lanes and trails now connect various parts of Dublin, Pleasanton, and Livermore, creating a large network that accommodates pedestrians and bikers. These paths not only offer us ways to enjoy the outdoors, but also promote alternative methods to getting around town. Today the Iron Horse Regional Trail occupies what was once the San Ramon Branch of the Southern Pacific Railroad. Much of this popular trail is already completed, and will extend 55 miles once finished.

To ease congestion BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) opened their east Dublin/Pleasanton station in 1997. The service proved so popular with commuters, that a West Dublin/Pleasanton station opened in 2011.

Do you enjoy looking at old maps?

Visit our local museums to peruse their archives:

Dublin Heritage Park & Museums,

Livermore's Carnegie Museum,

Pleasanton Museum on Main, and

Museum of the San Ramon Valley